LIVRE:The Project Gutenberg EBook of Morocco, by S.L. Bensusan

THROUGH A SOUTHERN PROVINCE

CHAPTER IX

Ripe grasses trammel a travelling foot;

The faint fresh flame of the young year flushes

From leaf to flower, and flower to fruit.

Even in these fugitive records of my last journey into the "Extreme West," I find it hard to turn from Marrakesh. Just as the city held me within its gates until further sojourn was impossible, so its memories crowd upon me now, and I recall with an interest I may scarcely hope to communicate the varied and compelling appeals it made to me at every hour of the day. Yet I believe, at least I hope, that most of the men and women who strive to gather for themselves some picture of the world's unfamiliar aspects will understand the fascination to which I refer, despite my failure to give it fitting expression. Sevilla in Andalusia held me in the same way when I went from Cadiz to spend a week-end there, and the three days became as many weeks, and would have become as many months or years had I been my own master—which to be sure we none of us are. The hand of the Moor is clearly to be seen in Sevilla to-day, notably in the Alcazar and the Giralda tower, fashioned by the builder of the Kutubia that stands like a stately lighthouse in the Blad al Hamra.

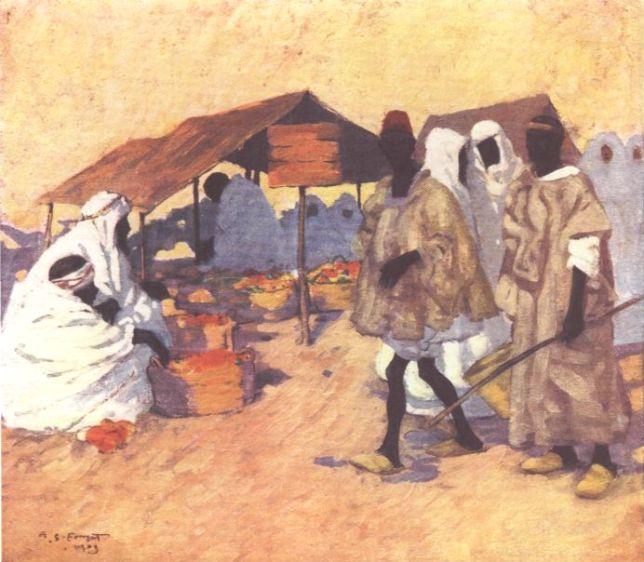

So, with the fascination of the city for excuse, I lingered in Marrakesh and went daily to the bazaars to make small purchases. The dealers were patient, friendly folk, and found no trouble too much, so that there was prospect of a sale at the end of it. Most of them had a collapsible set of values for their wares, but the dealer who had the best share of my Moorish or Spanish dollars was an old man in the bazaar of the brass-workers, who used to say proudly, "Behold in me thy servant, Abd el Kerim,[43] the man of one price."

The brass and copper workers had most of their metal brought to them from the Sus country, and sold their goods by weight. Woe to the dealer discovered with false scales. The gunsmiths, who seemed to do quite a big trade in flint-lock guns, worked with their feet as well as their hands, their dexterity being almost Japanese. Nearly every master had an apprentice or two, and if there are idle apprentices in the southern capital of my Lord Abd-el-Aziz, I was not fated to see one.

No phase of the city's life lacked fascination, nor was the interest abated when life and death moved side by side. A Moorish funeral wound slowly along the road in the path of a morning's ride. First came a crowd of ragged fellows on foot singing the praises of Allah, who gives one life to his servants here and an eternity of bliss in Paradise at the end of their day's work. The body of the deceased followed, wrapped in a knotted shroud and partially covered with what looked like a coloured shawl, but was, I think, the flag from a saint's shrine. Four bearers carried the open bier, and following came men of high class on mules. The contrast between the living and the dead was accentuated by the freshness of the day, the life that thronged the streets, the absence of a coffin, the weird, sonorous chaunting of the mourners. The deceased must have been a man of mark, for the crowd preceding the bier was composed largely of beggars, on their way to the cemetery, where a gift of food would be distributed. Following their master's remains came two slaves, newly manumitted, their certificates of freedom borne aloft in cleft sticks to testify before all men to the generosity of the loudly lamented. Doubtless the shroud of the dead had been sprinkled with water brought from the well Zem Zem, which is by the mosque of Mecca, and is said to have been miraculously provided for Hagar, when Ishmael, then a little boy, was like to die of thirst in the wilderness.

I watched the procession wind its way out of sight to the burial-ground by the mosque, whose mueddin would greet its arrival with the cry, "May Allah have mercy upon him." Then the dead man would be carried to the cemetery, laid on his right side looking towards Mecca, and the shroud would be untied, that there may be no awkwardness or delay upon the day of the Resurrection. And the Kadi or f'K'hay[44] would say, "O Allah, if he did good, over-estimate his goodness; and if he did evil, forget his evil deeds; and of Thy Mercy grant that he may experience Thine Acceptance; and spare him the trials and troubles of the grave.... Of Thy Mercy grant him freedom from torment until Thou send him to Paradise, O Thou Most Pitiful of the pitying.... Pardon us, and him, and all Moslems, O Lord of Creation."

On the three following mornings the men of the deceased's house would attend by the newly-made grave, in company with the tolba, and would distribute bread and fruit to the poor, and when their task was over and the way clear, the veiled women would bring flowers, with myrtle, willows, and young leaves of the palm, and lay them on the grave, and over these the water-carrier would empty his goat-skin. I knew that the dead man would have gone without flinching to his appointed end, not as one who fears, but rather as he who sets out joyfully to a feast prepared in his honour. His faith had kept all doubts at bay, and even if he had been an ill liver the charitable deeds wrought in his name by surviving relatives would enable him to face the two angels who descend to the grave on the night following a man's burial and sit in judgment upon his soul. This one who passed me on his last journey would tell the angels of the men who were slaves but yesterday and were now free, he would speak of the hungry who had been fed, and of the intercession of the righteous and learned. These facts and his faith, the greatest fact of all, would assuredly satisfy Munkir and Nakir.[45] Small wonder if no manner of life, however vile, stamps ill-livers in Morocco with the seal we learn to recognise in the Western world. For the Moslem death has no sting, and hell no victory. Faith, whether it be in One God, in a Trinity, in Christ, Mohammed, or Buddha, is surely the most precious of all possessions, so it be as virile and living a thing as it is in Sunset Land.

Writing of religion, I needs must set down a word in this place of the men and women who work for the Southern Morocco Mission in Marrakesh. The beauty of the city has long ceased to hold any fresh surprises for them, their labour is among the people who "walk in noonday as in the night." It is not necessary to be of their faith to admire the steadfast devotion to high ideals that keeps Mr. Nairn and his companions in Marrakesh. I do not think that they make converts in the sense that they desire, the faith of Islam suits Morocco and the Moors, and it will not suffer successful invasion, but the work of the Mission has been effective in many ways. If the few Europeans who visit the city are free to wander unchallenged, unmolested through its every street, let them thank the missionaries; if the news that men from the West are straight-dealing, honourable, and slaves to truth, has gone from the villages on the hither side of Atlas down to the far cities of the Sus, let the missionaries be praised. And if a European woman can go unveiled yet uninsulted through Marrakesh, the credit is due to the ladies of the Mission. It may be said without mental reservation that the Southern Morocco Mission accomplishes a great work, and is most successful in its apparent failure. It does not make professing Christians out of Moors, but it teaches the Moors to live finer lives within the limits of their own faith, and if they are kinder and cleaner and more honourable by reason of their intercourse with the "tabibs" and "tabibas," the world gains and Morocco is well served. When the Sultan was in difficulties towards the end of 1902, and the star of Bu Hamara was in the ascendant, Sir Arthur Nicolson, our Minister in Tangier, ordered all British subjects to leave the inland towns for the coast. As soon as the news reached the Marrakshis, the houses of the missionaries were besieged by eager crowds of Moors and Berbers, offering to defend the well-beloved tabibs against all comers, and begging them not to go away. Very reluctantly Mr. Nairn and his companions obeyed the orders sent from Tangier, but, having seen their wives and children safely housed in Djedida, they returned to their work.

The Elhara or leper quarter is just outside one of the city gates, and after some effort of will, I conquered my repugnance and rode within its gate. The place proved to be a collection of poverty-stricken hovels built in a circle, of the native tapia, which was crumbling to pieces through age and neglect. Most of the inhabitants were begging in the city, where they are at liberty to remain until the gates are closed, but there were a few left at home, and I had some difficulty in restraining the keeper of Elhara, who wished to parade the unfortunate creatures before me that I might not miss any detail of their sufferings. Leper women peeped out from corners, as Boubikir's "house" had done; little leper children played merrily enough on the dry sandy ground, a few donkeys, covered with scars and half starved, stood in the scanty shade. In a deep cleft below the outer wall women and girls, very scantily clad, were washing clothes in a pool that is reserved apparently for the use of the stricken village. I was glad to leave the place behind me, after giving the unctuous keeper a gift for the sufferers that doubtless never reached them. They tell me that no sustained attempt is made to deal medically with the disease, though many nasty concoctions are taken by a few True Believers, whose faith, I fear, has not made them whole.[46]

When it became necessary for us to leave Marrakesh the young shareef went to the city's fandaks and inquired if they held muleteers bound for Mogador. The Maalem had taken his team home along the northern road, our path lay to the south, through the province of the Son of Lions (Oulad bou Sba), and thence through Shiadma and Haha to the coast. We were fortunate in finding the men we sought without any delay. A certain kaid of the Sus country, none other than El Arbi bel Hadj ben Haida, who rules over Tiensiert, had sent six muleteers to Marrakesh to sell his oil, in what is the best southern market, and he had worked out their expenses on a scale that could hardly be expected to satisfy anybody but himself.

"From Tiensiert to Marrakesh is three days journey," he had said, and, though it is five, no man contradicted him, perhaps because five is regarded as an unfortunate number, not to be mentioned in polite or religious society. "Three days will serve to sell the oil and rest the mules," he had continued, "and three days more will bring you home." Then he gave each man three dollars for travelling money, about nine shillings English, and out of it the mules were to be fed, the charges of n'zala and fandak to be met, and if there was anything over the men might buy food for themselves. They dared not protest, for El Arbi bel Hadj ben Haida had every man's house in his keeping, and if the muleteers had failed him he would have had compensation in a manner no father of a family would care to think about. The oil was sold, and the muleteers were preparing to return to their master, when Salam offered them a price considerably in excess of what they had received for the whole journey to take us to Mogador. Needless to say they were not disposed to let the chance go by, for it would not take them two days out of their way, so I went to the fandak to see mules and men, and complete the bargain. There had been a heavy shower some days before, and the streets were more than usually miry, but in the fandak, whose owner had no marked taste for cleanliness, the accumulated dirt of all the rainy season had been stirred, with results I have no wish to record. A few donkeys in the last stages of starvation had been sent in to gather strength by resting, one at least was too far gone to eat. Even the mules of the Susi tribesmen were not in a very promising condition. It was an easy task to count their ribs, and they were badly in need of rest and a few square meals. Tied in the covered cloisters of the fandak there was some respite for them from the attack of mosquitoes, but the donkeys, being cheap and of no importance, were left to all the torments that were bound to be associated with the place.

Only one human being faced the glare of the light and trod fearlessly through the mire that lay eight or ten inches deep on the ground, and he was a madman, well-nigh as tattered and torn as the one I had angered in the Kaisariyah on the morning after my arrival in the city. This man's madness took a milder turn. He went from one donkey to another, whispering in its ear, a message of consolation I hope and believe, though I had no means of finding out. When I entered the fandak he came running up to me in a style suggestive of the gambols of a playful dog, and I was exceedingly annoyed by a thought that he might not know any difference between me and his other friends. There was no need to be uneasy, for he drew himself up to his full height, made a hissing noise in his throat, and spat fiercely at my shadow. Then he returned to the stricken donkeys, and the keeper of the fandak, coming out to welcome me, saw his more worthy visitor. Turning from me with "Marhababik" ("You are welcome") just off his lips, he ran forward and kissed the hem of the madman's djellaba.

A madman is very often an object of veneration in Morocco, for his brain is in divine keeping, while his body is on the earth. And yet the Moor is not altogether logical in his attitude to the "afflicted of Allah." While so much liberty is granted to the majority of the insane that feigned madness is quite common among criminals in the country, less fortunate men who have really become mentally afflicted, but are not recognised as insane, are kept chained to the walls of the Marstan—half hospital, half prison—that is attached to the most great mosques. I have been assured that they suffer considerably at the hands of most gaoler-doctors, whose medicine is almost invariably the stick, but I have not been able to verify the story, which is quite opposed to Moorish tradition. The mad visitor to the fandak did not disturb the conversation with the keeper and the Susi muleteers, but he turned the head of a donkey in our direction and talked eagerly to the poor animal, pointing at me with outstretched finger the while. The keeper of the fandak, kind man, made uneasy by this demonstration, signed to me quietly to stretch out my hand, with palm open, and directed to the spot where the madman stood, for only in that way could I hope to avert the evil eye.

The chief muleteer was a thin and wiry little fellow, a total stranger to the soap and water beloved of Unbelievers. He could not have been more than five feet high, and he was burnt brown. His dark outer garment of coarse native wool had the curious yellow patch on the back that all Berbers seem to favour, though none can explain its origin or purpose, and he carried his slippers in his hand, probably deeming them less capable of withstanding hard wear than his naked feet. He had no Arabic, but spoke only "Shilha," the language of the Berbers, so it took some time to make all arrangements, including the stipulation that a proper meal for all the mules was to be given under the superintendence of M'Barak. That worthy representative of Shareefian authority was having a regal time, drawing a dollar a day, together with three meals and a ration for his horse, in return for sitting at ease in the courtyard of the Tin House.

Arrangements concluded, it was time to say good-bye to Sidi Boubikir. I asked delicately to be allowed to pay rent for the use of the house, but the hospitable old man would not hear of it. "Allah forbid that I should take any money," he remarked piously. "Had you told me you were going I would have asked you to dine with me again before you started." We sat in the well-remembered room, where green tea and mint were served in a beautiful set of china-and-gold filagree cups, presented to him by the British Government nearly ten years ago. He spoke at length of the places that should be visited, including the house of his near relative, Mulai el Hadj of Tamsloht, to whom he offered to send me with letters and an escort. Moreover, he offered an escort to see us out of the city and on the road to the coast, but I judged it better to decline both offers, and, with many high-flown compliments, left him by the entrance to his great house, and groped back through the mud to put the finishing touches to packing.

The young shareef accepted a parting gift with grave dignity, and assured me of his esteem for all time and his willing service when and where I should need it. I had said good-bye to the "tabibs" and "tabibas," so nothing remained but to rearrange our goods, that nearly everything should be ready for the mules when they arrived before daybreak. Knowing that the first day's ride was a long one, some forty miles over an indifferent road and with second-rate animals, I was anxious to leave the city as soon as the gates were opened.

Right above my head the mueddin in the minaret overlooking the Tin House called the sleeping city to its earliest prayer.[47] I rose and waked the others, and we dressed by a candle-light that soon became superfluous. When the mueddin began the chant that sounded so impressive and so mournful as it was echoed from every minaret in the city, the first approach of light would have been visible in the east, and in these latitudes day comes and goes upon winged feet. Before the beds were taken to pieces and Salam had the porridge and his "marmalade" ready, with steaming coffee, for early breakfast, we heard the mules clattering down the stony street. Within half an hour the packing comedy had commenced. The Susi muleteer, who was accompanied by a boy and four men, one a slave, and all quite as frowzy, unwashed, and picturesque as himself, swore that we did not need four pack-mules but eight. Salam, his eyes flaming, and each separate hair of his beard standing on end, cursed the shameless women who gave such men as the Susi muleteer and his fellows to the kingdom of my Lord Abd-el-Aziz, threw the shwarris on the ground, rejected the ropes, and declared that with proper fittings the mules, if these were mules at all, and he had his very serious doubts about the matter, could run to Mogador in three days. Clearly Salam intended to be master from the start, and when I came to know something more about our company, the wisdom of the procedure was plain. Happily for one and all Mr. Nairn came along at this moment. It was not five o'clock, but the hope of serving us had brought him into the cold morning air, and his thorough knowledge of the Shilha tongue worked wonders. He was able to send for proper ropes at an hour when we could have found no trader to supply them, and if we reached the city gate that looks out towards the south almost as soon as the camel caravan that had waited without all night, the accomplishment was due to my kind friend who, with Mr. Alan Lennox, had done so much to make the stay in Marrakesh happily memorable.

It was just half-past six when the last pack-mule passed the gate, whose keeper said graciously, "Allah prosper the journey," and, though the sun was up, the morning was cool, with a delightfully fresh breeze from the west, where the Atlas Mountains stretched beyond range of sight in all their unexplored grandeur. They seemed very close to us in that clear atmosphere, but their foot hills lay a day's ride away, and the natives would be prompt to resent the visit of a stranger who did not come to them with the authority of a kaid or governor whose power and will to punish promptly were indisputable. With no little regret I turned, when we had been half an hour on the road, for a last look at Ibn Tachfin's city. Distance had already given it the indefinite attraction that comes when the traveller sees some city of old time in a light that suggests every charm and defines none. I realised that I had never entered an Eastern city with greater pleasure, or left one with more sincere regret, and that if time and circumstance had been my servants I would not have been so soon upon the road.

The road from Marrakesh to Mogador is as pleasant as traveller could wish, lying for a great part of the way through fertile land, but it is seldom followed, because of the two unbridged rivers N'fiss and Sheshoua. If either is in flood (and both are fed by the melting snows from the Atlas Mountains), you must camp on the banks for days together, until it shall please Allah to abate the waters. Our lucky star was in the ascendant; we reached Wad N'fiss at eleven o'clock to find its waters low and clear. On the far side of the banks we stayed to lunch by the border of a thick belt of sedge and bulrushes, a marshy place stretching over two or three acres, and glowing with the rich colour that comes to southern lands in April and in May. It recalled to me the passage in one of the stately choruses of Mr. Swinburne's Atalanta in Calydon, that tells how "blossom by blossom the spring begins."

The intoxication that lies in colour and sound has ever had more fascination for me than the finest wine could bring: the colour of the vintage is more pleasing than the taste of the grape. In this forgotten corner the eye and ear were assailed and must needs surrender. Many tiny birds of the warbler family sang among the reeds, where I set up what I took to be a Numidian crane, and, just beyond the river growths, some splendid oleanders gave an effective splash of scarlet to the surrounding greens and greys. In the waters of the marsh the bullfrogs kept up a loud sustained croak, as though they were True Believers disturbed by the presence of the Infidels. The N'fiss is a fascinating river from every point of view. Though comparatively small, few Europeans have reached the source, and it passes through parts of the country where a white man's presence would be resented effectively. The spurs of the Atlas were still clearly visible on our left hand, and needless to say we had the place to ourselves. There was not so much as a tent in sight.

At last M'Barak, who had resumed his place at the head of our little company, and now realised that we had prolonged our stay beyond proper limits, mounted his horse rather ostentatiously, and the journey was resumed over level land that was very scantily covered with grass or clumps of irises. The mountains seemed to recede and the plain to spread out; neither eye nor glass revealed a village; we were apparently riding towards the edge of the plains. The muleteer and his companions strode along at a round pace, supporting themselves with sticks and singing melancholy Shilha love-songs. Their mules, recollection of their good meal of the previous evening being forgotten, dropped to a pace of something less than four miles an hour, and as the gait of our company had to be regulated by the speed of its slowest member, it is not surprising that night caught us up on the open and shut out a view of the billowy plain that seemingly held no resting-place. How I missed the little Maalem, whose tongue would have been a spur to the stumbling beasts! But as wishing would bring nothing, we dismounted and walked by the side of our animals, the kaid alone remaining in the saddle. Six o'clock became seven, and seven became eight, and then I found it sweet to hear the watch-dog's honest bark. Of course it was not a "deep-mouthed welcome:" it was no more than a cry of warning and defiance raised by the colony of pariah dogs that guarded Ain el Baidah, our destination.

In the darkness, that had a pleasing touch of purple colouring lent it by the stars, Ain el Baidah's headman loomed very large and imposing. "Praise to Allah that you have come and in health," he remarked, as though we were old friends. He assured me of my welcome, and said his village had a guest-house that would serve instead of the tent. Methought he protested too much, but knowing that men and mules were dead beat, and that we had a long way to go, I told Salam that the guest-house would serve, and the headman lead the way to a tapia building that would be called a very small barn, or a large fowl-house, in England. A tiny clay lamp, in which a cotton wick consumed some mutton fat, revealed a corner of the darkness and the dirt, and when our own lamps banished the one, they left the other very clearly to be seen. But we were too tired to utter a complaint. I saw the mules brought within the zariba, helped to set up my camp bed, took the cartridges out of my shot gun, and, telling Salam to say when supper was ready, fell asleep at once. Eighteen busy hours had passed since the mueddin called to "feyer" from the minaret above the Tin House, but my long-sought rest was destined to be brief.

/https%3A%2F%2Fassets.over-blog.com%2Ft%2Fcedistic%2Fcamera.png)

/http%3A%2F%2Fdafina.net%2Fgazette%2Fsites%2Fdefault%2Ffiles%2Fimagecache%2F400xY%2Fachoura.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.telexpresse.com%2Fimagesnews%2F1351245014.jpg)

/http%3A%2F%2Fwww.aufaitmaroc.com%2Fpictures%2F0089%2F1057%2Fsimon_levy_07122011160839_medium.jpg%3F1323281718)